When We Were Young: Up to the Mountains, Down to the Villages

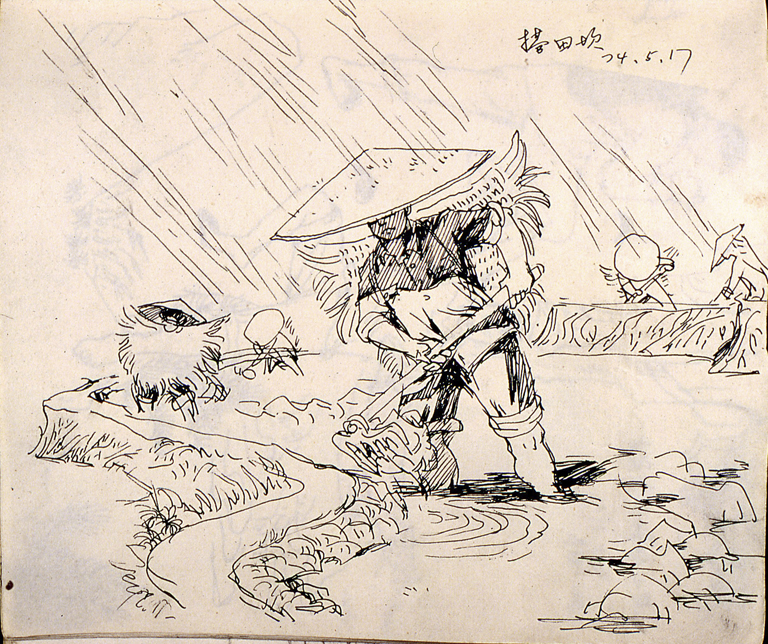

When I returned to China last summer, I found over twenty old sketchbooks. They were filled with my own drawings made during the Cultural Revolution when I was young. As I flipped through the pages, memories of my life in the countryside leapt out of the fading images: turbulent frenzy, then empty loss. Confusion and mindless obedience intertwined and shaped the fate of a whole generation. Our eventual awakening enabled us to re-appropriate our destinies.

Through these sketchbooks, that period re-emerges, realistically depicting my life experience, passion and thought. In search of art, I obtained an inner freedom and hope. In the analysis of my sketchbooks, I would like to approach the Cultural Revolution from personal, historical and political perspectives.

Frenzy

Our generation was nourished solely by the ideals of revolutionary heroism, growing up to become fanatics of the Cultural Revolution. We were taught to obey the absolute authority of the leader, to emulate the famous Lei Feng (a selfless soldier), to become screws and wheels of the revolution.

In 1966, Mao initiated the Cultural Revolution. His slogan for the youth was, “Revolution has no guilt, rebellion is justified.” The Red Guards were told to smash the old world and break from the influence of tradition and the West. This threw the country into complete disorder. Even President Liu Shaoqi was beaten to death in jail. At that time, I had just graduated from elementary school. I joined the revolution enthusiastically by painting Mao’s portraits and political propaganda posters.

The revolutionaries separated into two factions in 1967, each convinced it was truly loyal to Chairman Mao and the other was Mao’s enemy. The fighting escalated to the use of weapons, resulting in fatalities. My hometown of Chongqing was at the centre of the most concentrated fighting in the entire country. At night, I sat on a hill, watching the multi-coloured glow of bullets travelling over the river. It was a favourite pastime of children. In Shaping Park, there is a cemetery for the hundreds who died, the youngest were under the age of 16. My own cousin was shot to death under her bed in her apartment, when two factions fought to control the building. She was only 14 years old.

Up to the Mountains, Down to the Villages

In 1968, Mao’s faction gained control of the country and all of China became ‘red’. Having attained his goal of absolute power, his once beloved youths were useless to him. Letting them stay in the city became a big social problem, Mao developed an ingenious solution. It all began on December 22, when Chairman Mao decreed, “It is very necessary for urban educated youth to go to the countryside and learn from the poor and middle peasants. We must persuade urban cadres and everyone else to send their children who have graduated from middle schools, high schools and universities to the rural areas. We need to mobilise. Comrades in the countryside should welcome them warmly.” Thereafter, over seventeen million young people in the cities were transformed from Red Guards to subjects of re-education. I was one of them. This re-education was to take place in the countryside and remote regions of China. The slogan “Up to the Mountains, Down to the Villages” became the title of another political movement lasting ten years. And we, the youth, upholding the framed oil painting of “Mao going to Anyuan,” marched onto a path of unity with peasants and workers. On this path, individual destinies became inevitably immersed in the larger destiny of a generation.

My brother, my sister and I all went to the countryside, leaving my mother alone at home. Our broken family was common during that time. Ten percent of the population was comprised of ‘educated youth.’ Suddenly, they disappeared from the city. My brother and I were sent to the Daba Mountain Region between the borders of Shaanxi and Sichuan province. Once the base for the Red Army in the 1930s, it was the most remote, poor and backward region in China. There were no roads and no electricity. All supplies had to be transported by people.

The village of one hundred people was situated halfway up a mountain. We lived in a courtyard house with six families. Every time it rained, the roof would leak. The basic functions of life, such as cooking, required measuring rice and gathering fuel. Because most trees were cut down during the Great Leap Forward to make iron and steel in 1958, we had to climb to the top of the mountain to get tree branches. With over a hundred and fifty pounds of fuel on our backs, we walked over 30 kilometres.

When we first arrived, we had only one idea, to “roll in mud and gain a red heart” doing the dirtiest and hardest labours. We worked from sunrise to sunset, amassing enough points for the equivalent of eight cents (RMB) in wages. During spring and fall, we had to work around 20 hours a day, there was not enough time for proper sleep. We dozed on a bamboo bed by the field. At this time, we had no food because the old supplies were gone and the new food was not yet ready for consumption. We ate whatever we could find.

In the name of the revolution, thousands of sent-down youth died. For example, in Inner Mongolia, sixty-nine youths died while trying to put out a wildfire without water or equipment.1 In Guandong province, hundreds of youths were ordered to form a human wall in the face of a tsunami. They all drowned.2 Hundreds of female youths were raped by local cadres. Hundreds were falsely accused of crimes by local government. Each individual of our entire generation matured through these tragedies and hardships.

Our revolutionary fervour was soon chilled by the reality of daily life. Hardship and isolation forced us to raise questions about the state of the Cultural Revolution. Critical reflection led to doubt, but it allowed us to rediscover ourselves and the Chinese nation. We could not express this loss of complete faith for fear of being branded a counter-revolutionary. My sketchbooks are silent witnesses of this larger transformation.

No Leisure Life

Even though the countryside was far from the cosmopolitan centres of culture and politics, waves of the political movement could still reach the faraway border regions. Aside from farming, we participated in revolutionary critiques and the production of propaganda. We wrote big character slogans on houses and rocks, and painted propaganda images on walls. I knew they were meaningless, but I still did it because it was better than hard physical labour. Also, it could brighten our political reputation for a chance to return to the city.

There was no cultural life in the countryside. We could only write letters and wait for replies, one was received every month. Each letter was read over and over. They were the only way to communicate with the outside world. But once every year, we were allowed to return home and visit our families. This was the most important event. Not only were we glad to see our loved ones, but the change from a simple rural environment to a civilised urban setting was also crucial. In the city, we filled ourselves with vivid memories to last us for another year. The idea of home, a place where we belonged and would like to be, sustained us in the countryside everyday. We were exiles.

We were lonely, living in one production unit far from friends. The most interesting thing to do was to visit each other. We gathered in groups of ten or twenty to drink and eat, and to forget our troubles. Every two months, the local government also organised meetings for educated youths in order to better monitor them. These meetings were designed to study politics, but no one was interested, it became another way for youths to socialise. Whenever we saw older educated youths who had married locals and had assimilated completely into peasant life, we saw a bleak future waiting for us. In contrast, when new youths came to our region, our loneliness was eased.

Watching movies was a rare event. Every year, there were one or two chances. They were all shown outside in one place. In order to see a film we had probably already seen several times, we walked long distances in the dark. Most movies were prohibited from being shown. The only foreign films permitted were along the lines of “Lenin in 1918.” The only reason we liked this movie was because of the ten seconds of “Swan Lake” and the Bolshevik promise of “milk and bread.” One revealed the beauty of art and romantic love, while the other displayed the irony of our struggle for survival.

Because of the tight controls on culture and art, there were only a few revolutionary performances we could see. Each local region organised their own “Chairman Mao’s thought entertainment group” to perform reproductions of the ‘eight model’ operas and ballets selected by Mao’s wife Jiang Qing. My brother and I joined our regional group, toured the villages and performed for peasants. Although the peasants knew more about farming, we distinguished ourselves with our superior artistic talent. In their eyes, we gained value and respect. Aside from the entertainment groups, there were athletic teams. I joined the regional basketball training camp because I was tall. It was so tiring that we had hardly any energy to change clothes. But we could eat well, there was meat in every meal. This was the best life at that time because we had never been full before.

Playing cards was not allowed in China, but in the countryside we could get away with it. In our little spare time, we played cards together. The loser had to stick paper on their face, or crawl under tables. We would also use cards to tell fortunes, but our real future was uncertain. We were stranded in what seemed like a perpetual limbo.

Most novels in the city were banned, but there was more freedom in the countryside. Youths brought illegal books to read and to distribute. People would write collective novels themselves. For example, “An Embroidered Shoe” and “The Second Handshake” traveled across the country. They were all romantic stories and were, therefore, very popular. At that time, even the word ‘love’ could not be said between lovers. The author of “The Second Handshake,” Zhangyang, was sent to jail for four years.3

We were only allowed to sing revolutionary songs, but in the reality of the countryside, these songs could no longer awaken our passion. Everyone liked to sing Western folk songs and copied songs from each other. Later, people began to compose their own songs; for example, “The song of Chongqing” was composed by an unknown educated youth. The songs were filled with longing for home and spoke of uncertain futures. They were soon accused of being against the revolution. The composer of “The song of Nanjing,” Renyi, was sent to jail for ten years.4

I became a substitute teacher, a common occupation for educated youth. School conditions were very poor. Some classrooms had no windows. In winter, it was so cold that students got frost bite on their fingers. They also had to bring their own pots and pans to cook food for themselves. Despite these harsh conditions, I liked their sincerity and innocence and tried my best to teach them well. We built good relationships. At night, I also had to teach literacy to the peasants. In the daytime, they taught me the skills to be a farmer. Through teaching, the gap between us became smaller.

The Theory of Birth

Among the educated youth, many were born into ‘Black Families.’ A person’s worth was determined by their birth. If you were born into the families of workers, peasants, soldiers or cadres, you were automatically a ‘Red’ revolutionary. If you were born into the families of landlords, capitalists, counter-revolutionaries and intellectuals, you were a part of ‘Black Families,’ enemies of the people. This categorisation would continue from one generation to the next. Your birth determined your future. An educated youth, Yu Luoke, wrote an essay criticising the “Theory of Birth,” gaining widespread support among youth. Yu Luoke was subsequently accused of being a counter-revolutionary and executed in 1970 at the age of 27.5

Beginning in 1972, the government started to select youth to return to the city to work. But everyone had to go through a political background check. If your birth was bad, then there was no chance to go back to the city. I was one of those born into a ‘Black Family.’ In 1957 during the Hundred Flowers Blooming movement, my father was accused of being a Rightist and a historical counter-revolutionary. For thirty years, he lived in a labour camp. Because of this, our family was discriminated against and stripped of our rights. The children of Black Families before and during the Cultural Revolution had no choice but to go to the countryside.

Because I drew, played basketball and worked hard, schools and factories all liked me and wanted to recruit me. But when they saw my political background, they couldn’t hire me. I went through five of these rejections. There was a policy that said among all the children born into ‘Black Families,’ there was five percent that could be re-educated. In the beginning, I believed that if I worked hard, I could fit into this category and have a chance to go back to the city. But reality crushed my dreams. My shame of being born into a ‘Black Family,’ wrestled with an almost perverse desire to become the son of a ‘Red Family,’ master of the state. My innermost longings surfaced onto the white pages of my sketchbooks.

Hope

Faced with a bleak reality, I turned to my art. I started to record my thoughts and experiences through drawing. In the daytime, during breaks from labour, I would draw other farmers and the landscape. At night, under the light of an oil lamp, I would draw my inner thoughts. Through these sketches, I began to develop an independent will. My concepts, language and expressions in art began to shift. According to revolutionary theory, the laws of artistic achievement were “red, smooth, bright” and “tall, robust, perfect.” The practice of this revolutionary art became hollow and meaningless. It was soon abandoned in my mind. A doubt for the revolution, dissatisfaction with reality and hope for the future, surfaced in my sketches. The emotions embedded in my drawings reveal a layered tension of history and environment. They depict a youth’s disillusionment and the beginning of a real life. The quest for art became a search for self and a medium of communication between the outer world and my spirit. Eventually, an inner art triumphed over the external environment that deprived me of self-worth.

My four long years in the countryside taught me how to transform negatives into positives and to never lose hope. In my darkness, I remembered my mother’s words, “Time will change everything.” But the impatience of my youth led me to wonder how long I had to wait for change. It is only after this period of my life, when I realised it was my minute hope that carried me through time.

— Gu Xiong, 2002

- Liu Xiaomeng and Ding Yizhuang, et al, Zhongguo Zhiqing Shidian (Record of Chinese Educated Youth) (Chengdu: Sichuan Renming Chubanshe (Sichuan People’s Publishing House), 1995), 649.

- Wang Mingjian, Shangshan Xiaxiang: Shanshi Nian (Up to the Mountains Down to the Villages: 30 Years) (Beijing: Guangming Ribao Chubanshe (Guangming Daily Publishing House), 1998), 90.

- Liu and Ding, 621.

- Ibid., 615.

- Liu and Ding, 757